Elsewhere in my paltry collection of rare and/or antique books is a 1907 copy of Modern Painting, Hardwood Finishing and Sign Writing, attributed to George D. Armstrong, Frederick Hodgson, and Frances Delamotte. I write "attributed", because it seems that some significant portion of the 434 page section on "modern painting", also appears in The Painters' Encyclopaedia : Containing Definitions of All Important Words in the Art of Plain and Artistic Painting, dated 1887, and attributed to Franklin B. Gardner, whose name doesn't appear, near as I can tell, in the book I've got. I don't know anything about any of those names, and far be it from me to besmirch their doubtlessly fine reputations by shouting "pirates!". Fact is, I haven't really read much of the book, anyway: the "sign writing" portion is a dozen or so pages of not especially insightful commentary on which letter forms are best used where, and an assortment of not especially attractive "Plain and Ornamental and Ancient and Mediaeval Lettering from the Eighth to the Twentieth Century". Look through the internet archive for some of the best, and, arguably, the worst (or, if that's too harsh, perhaps the least useful) alphabets in the slender appendix.

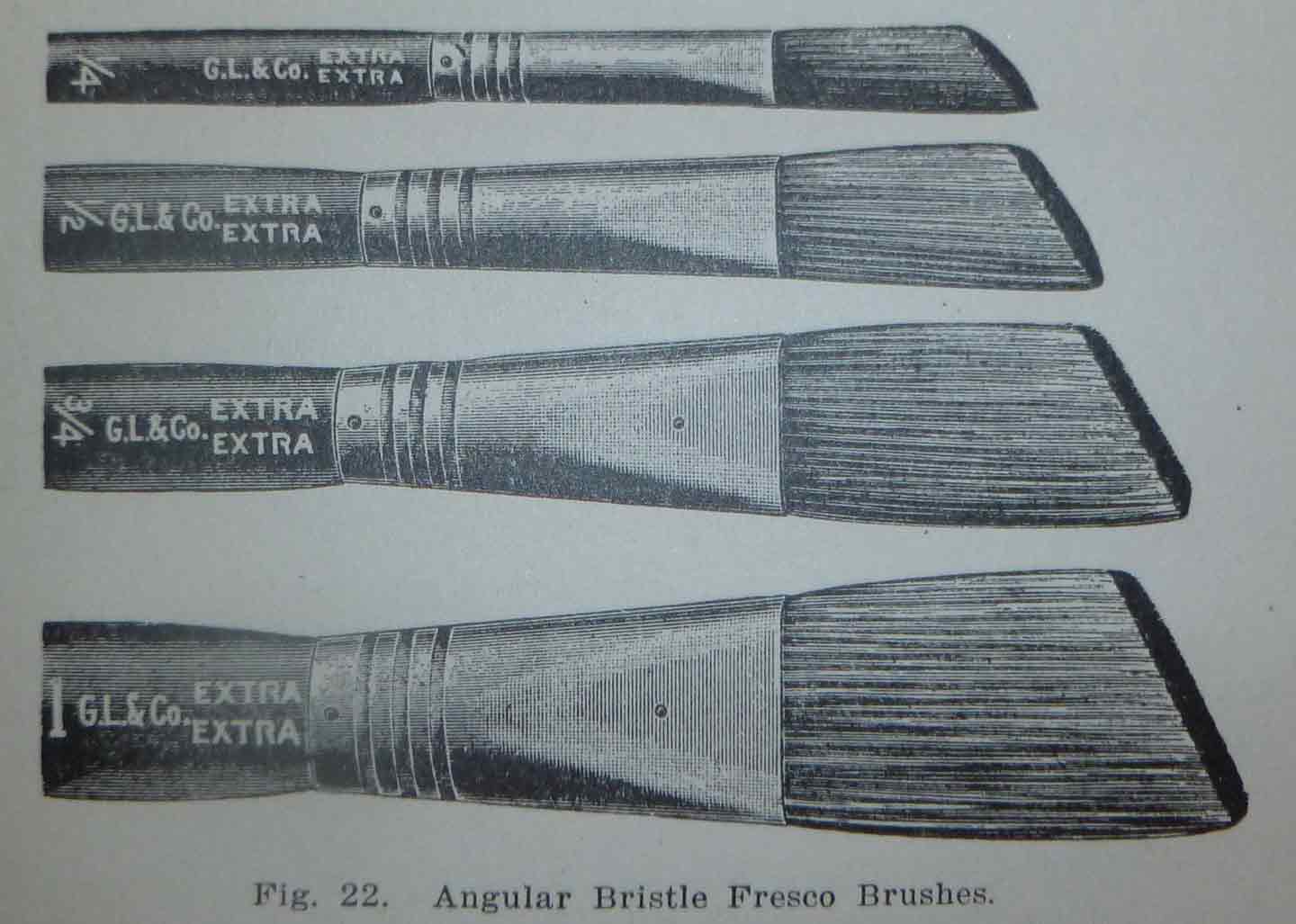

There are, on the other hand, a lot of beautiful engravings throughout the book, including ten pages of a variety of wallpaper hangers' tools. I especially enjoyed these engravings of successive stages of faux woodgraining:

Elsewhere in my paltry collection of rare and/or antique books is a 1907 copy of Modern Painting, Hardwood Finishing and Sign Writing, attributed to George D. Armstrong, Frederick Hodgson, and Frances Delamotte. I write "attributed", because it seems that some significant portion of the 434 page section on "modern painting", also appears in The Painters' Encyclopaedia : Containing Definitions of All Important Words in the Art of Plain and Artistic Painting, dated 1887, and attributed to Franklin B. Gardner, whose name doesn't appear, near as I can tell, in the book I've got. I don't know anything about any of those names, and far be it from me to besmirch their doubtlessly fine reputations by shouting "pirates!". Fact is, I haven't really read much of the book, anyway: the "sign writing" portion is a dozen or so pages of not especially insightful commentary on which letter forms are best used where, and an assortment of not especially attractive "Plain and Ornamental and Ancient and Mediaeval Lettering from the Eighth to the Twentieth Century". Look through the internet archive for some of the best, and, arguably, the worst (or, if that's too harsh, perhaps the least useful) alphabets in the slender appendix.

There are, on the other hand, a lot of beautiful engravings throughout the book, including ten pages of a variety of wallpaper hangers' tools. I especially enjoyed these engravings of successive stages of faux woodgraining:

I wonder how useful those illustrations proved to be for the faux finishers of a century ago. I think they'd look good framed. And hung on a faux oak wall.

But honestly: I only mention this book, to take opportunity to recount the following passage, on the harvesting of boar bristles for fine paintbrushes. Most of the brushes we use at New Bohemia are called lettering quills, and, rather than Russian boar bristles, they consist of Russian squirrel tail hair, which I choose to believe is harvested harmlessly, with a few snips of scissor, only to regrow endlessly, on the wildly flicking tails of romping, happy, well-fed, feral squirrels--to say nothing of the geese who selflessly relinquish a few feathers, into the hollow shafts of which the squirrel tail hair is stuffed, and wire-bound to a stick... I could go on--it's all very wholesome--but I choose instead, every so often, to torment the vegans who work with me, by reading aloud of the bristle harvest. It may seem especially cruel of me, since Vegan Ken is the guy who gave me the book, in the first place, but actually, he rather seems to enjoy hearing the tale told, again and again--he even lobbies for it:

It would be an almost endless task to illustrate and describe all of the many varieties of paint and varnish brushes, and a few of the principal ones only will receive attention here. Russia is the great bristle growing country, and her exports reach as high as 5,000 tons of this commodity every year. Hogs in countless herds roam the deep Muscovite forests, where the oak, the pine, the beech, larch and other nut bearing trees cover the ground with acorns and nuts to the depth of a foot or more. But these swine are not all of value for their bristles. The perfect bristle is found only on a special race, and that race fattened in a certain way. On the frontiers of civilization all over the Muscovite territory are the government tallow factories where animals reared too far from the habitation of men to be consumed for human food are boiled down for the sake of their fat. The swine are fed on the refuse of these tallow factories at certain seasons, and become in prime condition after a few months' feeding. It is from these animals that the bristles of commerce mainly come. When the swine are fattened, and their bristles in fine color, they are driven in kraals so thickly that they can scarcely stand--irritated and goaded by the herdsmen till they are sullen with rage--kicking, striving, struggling and scrambling together in feverish rage, they are seized one by one, by the kak koffs, a class of laborers educated to plucking swine, and their bristles pulled out by the roots. The perspiration into which the poor creatures are thrown by their exercise causes their bristles to yield easily. The process is pleasant neither to the eye nor the ear. The hog strenuously resists with loud outcries, and vehement opposition. It does no good. Once seized, he is instantly divested of his clothing and then immediately released, goes grunting off to the woods.